|

Welcome to my 'zine tree! Here in my studio, I've got this wire-y thing hanging above my computer desk chock-full of paper goods that have kept me curious. Instead of filing one thing away when I wish to add something, I've decided to do these features about some of the creators' works on the tree. There's a little bit of everything up there - some photography, some stickers, some floppy comics, but most of it is cartoon and comics art and all of it is independently produced. |

|---|

- Writer |

|---|

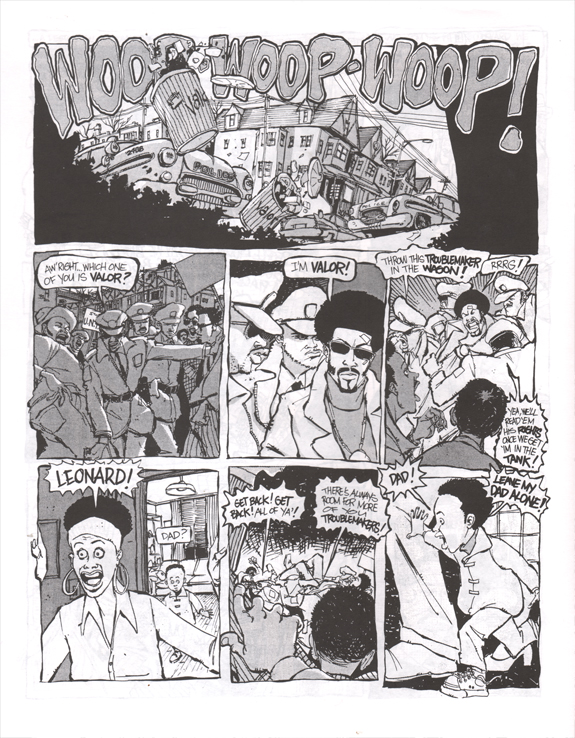

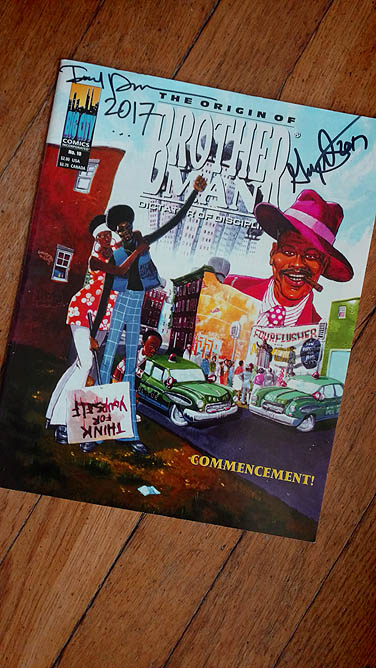

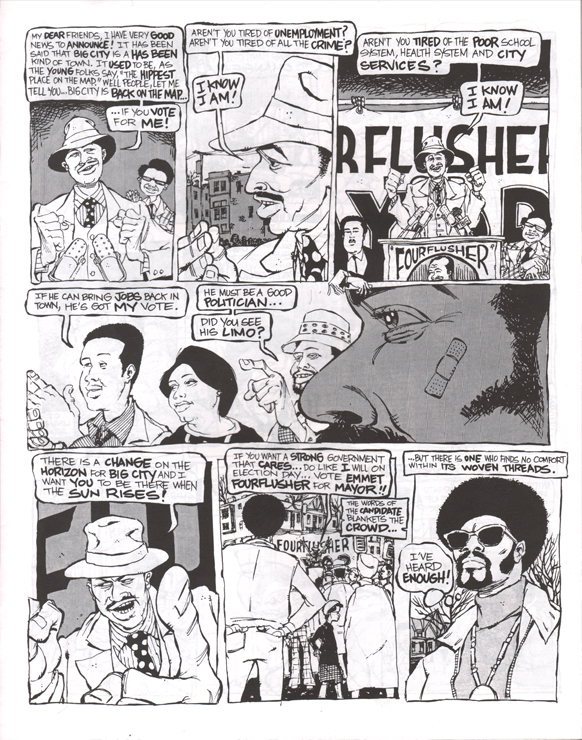

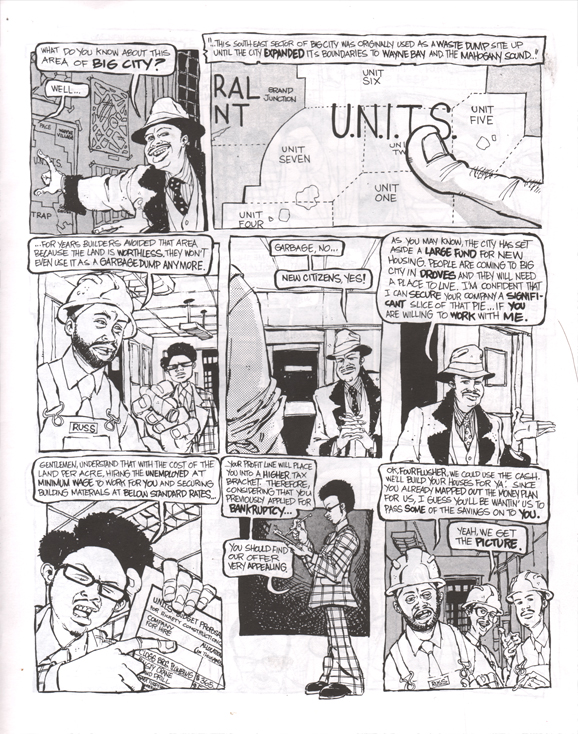

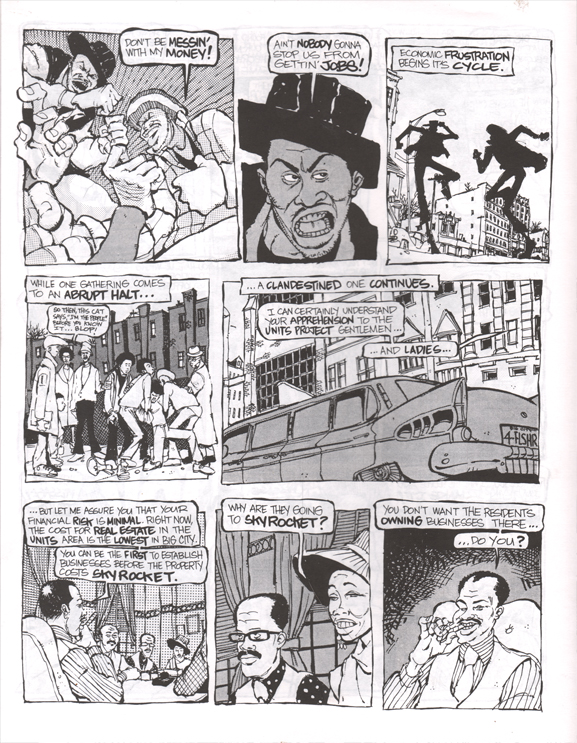

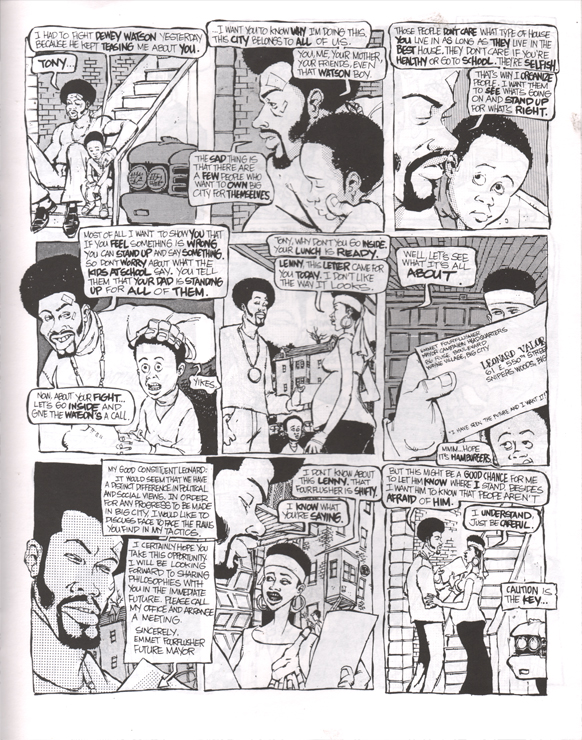

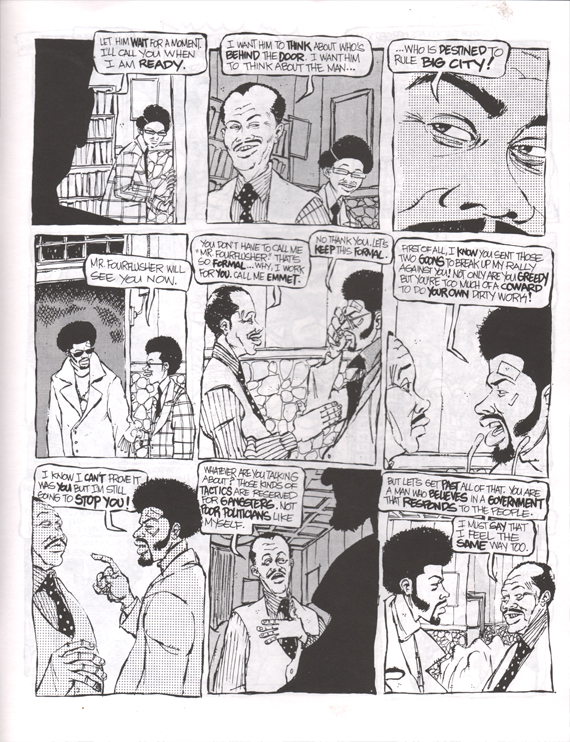

AG: This Brotherman comic, from 1994, is about a corrupt politician named Emmet Fourflusher, who is running for mayor of Big City in 1974, who finds a worthy enemy in the skeptical and virtuous Leonard Valor, a social studies teacher and community organizer. |

|

AG: Valor finds himself up against his own peers and his job promotion threatened when he disagrees with Fourflusher about a building development plan in a neighborhood called Snipers Woods and eventually turns to activism: |

|

AG: Could you recall the political climate from when you wrote this story? Were there parallels from the time that might have inspired you? (also, feel free to expand here if there were multiple references) |

Sims: The influence of Brotherman is drawn from the experiences of me and my brothers going all the way back to our days growing up in Philadelphia and visiting our cousins in Jersey City, NJ. It is difficult to pinpoint what time period or events played a significant role in how the stories and styles were crafted. The greatest influence was our home life, our parents, our siblings, and interactions in school and with friends. The politics of the times have always been consistent but our evolution as young men changed with times, eventually constructing the mindset that eventually created Brotherman. Of course, when you look at the art styling and reference, it is predominantly from the 90s but those who read into it will be able to see generational thinking and sensibilities in the writing and presentation. In 2016, we released the Brotherman graphic novel, Revelation. Longtime fans will be able to tell the difference in style, in the writing, and most importantly, the presentation of the book. The graphic novel tells the first part of the origin story of Brotherman, pointing the spotlight on Antonio Valor’s parents, Leonard and Carmen. While the story message is consistent, the time between issue #11 (1996) and the graphic novel (2016) is twenty years of personal growth, experience, skill development, and time to think critically about the direction of Brotherman. When we returned to Brotherman, we knew it had to be presented differently, to show how we have evolved as artists and how we looked at the world. We constructed a 300-page story that delved deeply into all of the elements of the Brotherman Universe. This allowed for the creation of the Founders of Big City, their currency, and an expanse of Brotherman products like The Cold Hard Cases of Duke Denim detective series (Duke Denim as a private detective prior to becoming the District Attorney). It is a good feeling when people can draw parallels to what is happening in real-time to the stories in Brotherman. The philosophy is to identify timeless themes of human behavior and embody them within engaging characters. Add Dawud’s artwork and again, the audience becomes another citizen in Big City. I found that to be a better way to go rather than take stories from the headlines and try to incorporate Brotherman into them. |

AG: I had one, and only one issue of “Brotherman” as a kid, which I got from Haneef’s Bookshop — an afro-centric bookstore in downtown Wilmington, DE. The shop was across the street from where we went regularly to pick up takeout fried chicken. When we’d go to pick up food, I’d have to beg to be allowed to cross the street on my own to go over to Haneef’s and look at the comic books. It felt like such an extra effort; when we went to the mall, there was a comics shop, chock-full of mainstream superhero comics.

AG: In America, young girls are given dolls that are designed to reflect their identities, to help them establish selfhood. Comics provides a similar mirroring experience for young boys – heroes matter. However, by the time I saw a Brotherman comic, I had already read Captain America comics of my brother’s. The suits had such a similarity (despite the lack of color in Brother comics), I’d sometimes stare at the drawings of Brotherman in this very very innocent way -- not increduously wondering if I’d somehow been duped into reading a clone comic, but perhaps so already utterly consigned to the hero myth of Captain America, that the internal differentiation between the two heroes was not a deliberation that I was capable of making.

Can you talk about your family and their choice to make these comics?

Sims: Before Brotherman, my brothers and I always collaborated on projects. We each had distinct and unique talents that worked well, both independently and as a group.

So the creation of Brotherman and the business was not new, it just happened to find the right time to come together. At the time of the creation of Brotherman, I was living in Delaware and my brothers in New Jersey. The original plan was to create a comic-style advertisement for their air brush t-shirt business in advance of the New York Black Expo. The plan changed with the question as to whether we could create and produce a comic book in time for the expo. Everybody did their part and we had a very successful outing at the NY Black Expo. As we pressed further, our parents also assisted, helping us with traveling, production, marketing, and distribution.

With regards to Brotherman’s origin, our goal was to create an epic tale of desire, sacrifice, courage, and purpose without the use of serums or intergalactic intervention. Our audience appreciated the genuine experience of the world of Brotherman. This isn’t to say that there aren’t “comic-booky” things happening in the story but the overall thrust is different from what may be currently out there. That gives Brotherman his uniqueness.

AG: How would you summarize the response to Brotherman’s origin story? Did you receive any letters about this particular issue? Personally, why do you think it spoke to your readers?

Sims: The response has been tremendous. People have expressed feelings of exhaustion after reading the first part. Some pointed out how emotional the story was. Others were full of anticipation for the next two installments. In addition to letters, we get people making video messages, or other messages through social media. It is humbling to read or hear people’s positive comments. It makes one very conscious of what you create.

Again, I think people can see themselves and their experiences in the stories of Brotherman. Not only in the main stories but also in the side stories and the action taking place in the background. That is the fun of the Brotherman experience.

Sims: It was a fun and exciting venture. For me, it was a great project for my brothers and me. It was a new venture. In the beginning, I do not even think we put much thought into what the larger market of comics really were, especially me. After the other African American books came out, we found that to be great because we all have different stories to tell. I had begun collecting some of the other books and they were all different in their stories, styles, and deliveries. That was important to the market, dismissing the notion that we would all write about “hard times in the ghetto”.

Today, thanks to changes in technology, the numbers of African American writers and artists have more platforms to present their work to the public. Venues such as groups on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Wordpress, and others allow anyone with a story to tell it, get feedback, and develop a fan base. There are still challenges with distribution to traditional markets but we (African Americans) have always found our way around the traditional system.

AG: Did Big City Comics (publisher of Brotherman) contemplate a mainstream windfall for themselves at all, or did that seem impossible, given the edgy thrust of its stories and themes?